Regenerative Sustainability Learning

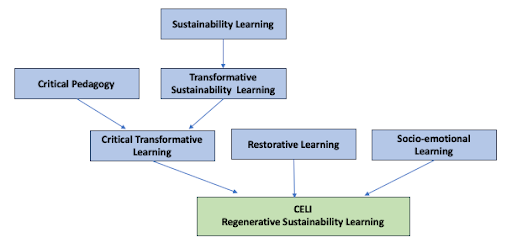

CELI’s approach might best be described as regenerative sustainability learning: an approach that combines critical pedagogy, with transformative sustainability learning, restorative learning, and that recognizes that humanity’s survival depends on regenerating the severed connections between, within, and across human beings and nature.

Critical pedagogy has been shown to improve science engagement, agency and learning of underrepresented minority students by incorporating “urgent issues of social and environmental justice identified by [the students’] communities” into science teaching (Morales-Doyle 2015). Critical pedagogy “provides a theoretical and practical framework that produces openings for youth to develop deep place-centered scientific knowledge and apply this knowledge in solving sustainability concerns” (Dimick 2016). Yet enacting critical pedagogy requires that we confront oppressed students’ fears and anger head on, even in young students. Davis and Schaeffer (2019) who conducted a critical pedagogy case study of Black 4th and 5th graders living Flint Michigan’s water justice crisis, concluded: “We do not see children’s expressions of fear and anger in this case as a legitimate rationale for limiting justice-oriented science pedagogy in elementary classrooms... Children in Riverview and Flint have a right to feel angry.” Our STEM-NET focus groups went further, indicating that students must be given the time and opportunity within the learning environment to process their fear and anger, and understand its basis, if they are to transcend its crippling effects. We note that a multi-disciplinary approach to climate education can greatly facilitate that opportunity, enabling the processing of emotional reactions to facts through art, writing, media, etc.

The goal of sustainability education is education to enact personal and societal transformations to sustainability: transformative sustainability learning that changes thinking, behaviors, and institutions (Sipos et al. 2008). Burns (2015) argues for transformative sustainability learning that embodies critical pedagogy and is collaborative in nature, a fusion that Lang (2004) calls critical transformative learning. According to Burns, and foundational to CELI’s design: “How sustainability is taught has a profound influence on the kind of learning that takes place and the impact it has in the world. Sustainability pedagogy is...a tool for creating transformational sustainability learning that is thematic and co-created, critically questions dominant norms and incorporates diverse perspectives, is active, participatory and relational, and is grounded in a specific place.”

Lang (2004) argues further that restorative learning is an essential element of critical transformative learning for revitalizing citizen action, particularly action toward a sustainable society.” Specifically, she argues that transformation necessarily emerges from cognitive disequilibrium (“a disorienting dilemma”), and that surviving that disorientation involves “a restoration to a rightful ethical place” in the learner and with respect to society at large. That is, this restoration realigns with ethics that were not missing, but were submerged by living within the discordant culture and practice of our times. In other words, this restorative learning is a kind of coming home to an original state of goodness and deep understanding of interconnection.

Looking more closely, it is living in that state of cognitive dissonance – a state in which how we live is so different from how we know we deep down that should live – that causes the disengagement and disaffection we see in our students and ourselves, creating a confusion of purpose that prevents the full flowering of their, and our, beings. A good education can help one recognize the dissonance and its cause, as the first step toward healing. The second step is providing the modeling and opportunity to remove the dissonance. The latter, of course, is the biggest challenge, because removing the cause requires changing culture at a near-global level. However, as Joan Baez said “Action is the antidote to despair” – a position supported by the American Psychological Association (APA 2023), which cites evidence that engaging young people in collective climate action can reduce depression and anxiety, and improve academic engagement.

In fact, the APA’s (2023) recommendations for school climate curriculum, mirror CELIs educational philosophy: “To prepare them for this future, children need to learn the facts of climate change based on strong scientific consensus. School lessons about climate change do not have to be bleak, and can emphasize hope and efficacy (Baker et al. 2021). When children learn the sobering scientific facts about the climate crisis, their emotional well-being appears to be better when they believe that their own actions can make a difference and that their engagement with the issue can be a source of meaning and importance in their lives and their communities (e.g., Ratinen & Uusiautti 2020; Baker et al. 2021). A study in Israel found that school lessons that explicitly promoted hope and engaged children in hands-on learning to protect the environment were not only linked to higher pro-environmental behavior from the children but to higher levels of satisfaction with their school experience (Kerret et al. 2020). And after-school programs that emphasized climate action also resulted in children feeling more empowered, motivated, and positively engaged (Trott 2020; Trott 2022).”

Our CELI work takes this evolution of educational theory one step further, advocating for regenerative sustainability learning. We cannot just stop doing bad things and preserve the remaining good things if we are to transcend the polycrisis. And we do not seek to attain a state of sustainable misery. We need to ‘restore’ nature and society to a much better state, one that is joyous, just, resilient, and life supporting, revitalizing that which has been destroyed. We need to restore anew those systems that are continually creating and recreating the crises, systems on the verge of collapse both ecologically and socially. Nor can we transcend the trauma without joy. To maintain commitment and resolve, we need learning that regenerates our spirits and our communities, as well as our living world, and our understanding of our interconnectedness to it all. That is the goal of regenerative sustainability learning.

References:

- APA (2023). Mental Health and Our Changing Climate Children and Youth Report 2023. American Psychological Association, Climate for Health, and EcoAmerica. Available online.

- Baker, C., & Clayton, S. (2021). Educating for hope: Building climate change resilience in the middle school classroom. Unpublished thesis.

- Burns, H. (2015). Transformative sustainability pedagogy: Learning from ecological systems and indigenous wisdom. Journal of Transformative Education, 13(3), 259-276. Available online.

- Davis, N.R., & Schaeffer, J. (2019). Troubling troubled waters in elementary science education: Politics, ethics & Black children’s conceptions of water [justice] in the era of Flint. Cognition and Instruction, 37:3, 367-389. Available online.

- Dimick, A.S. (2016). Exploring the potential and complexity of a critical pedagogy of place in urban science education. Science Education, 100(5), 814-836. Available online.

- Kerret, D. et al. (2020). Two for one: Achieving both pro-environmental behavior and subjective well-being by implementing environmental-hope-enhancing programs in schools. The Journal of Environmental Education, 51(6), 434-448. Available online.

- Lang, E. (2004). Transformative and restorative learning: A vital dialectic for sustainable societies, Adult Education Quarter, 54(2), 121-139. Available online.

- Morales‐Doyle, D. (2017). Justice‐centered science pedagogy: A catalyst for academic achievement and social transformation. Science Education, 101(6), 1034-1060. Available online.

- Ratinen, I., & Uusiautti, S. (2020). Finnish Students’ Knowledge of Climate Change Mitigation and Its Connection to Hope. Sustainability, 12(6), 2181. Available online.

- Trott, C. D. (2020). Children’s constructive climate change engagement: Empowering awareness, agency, and action. Environmental Education Research, 26(4), 532-554. Available online.

- Trott, C. D. (2022). Climate change education for transformation: Exploring the affective and attitudinal dimensions of children’s learning and action. Environmental Education Research, 28(7), 1023-1042. Available online.

- Sipos, Y., et al. (2008). Achieving transformative sustainability learning: engaging head, hands and heart". International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(1), 68-86. Available online.